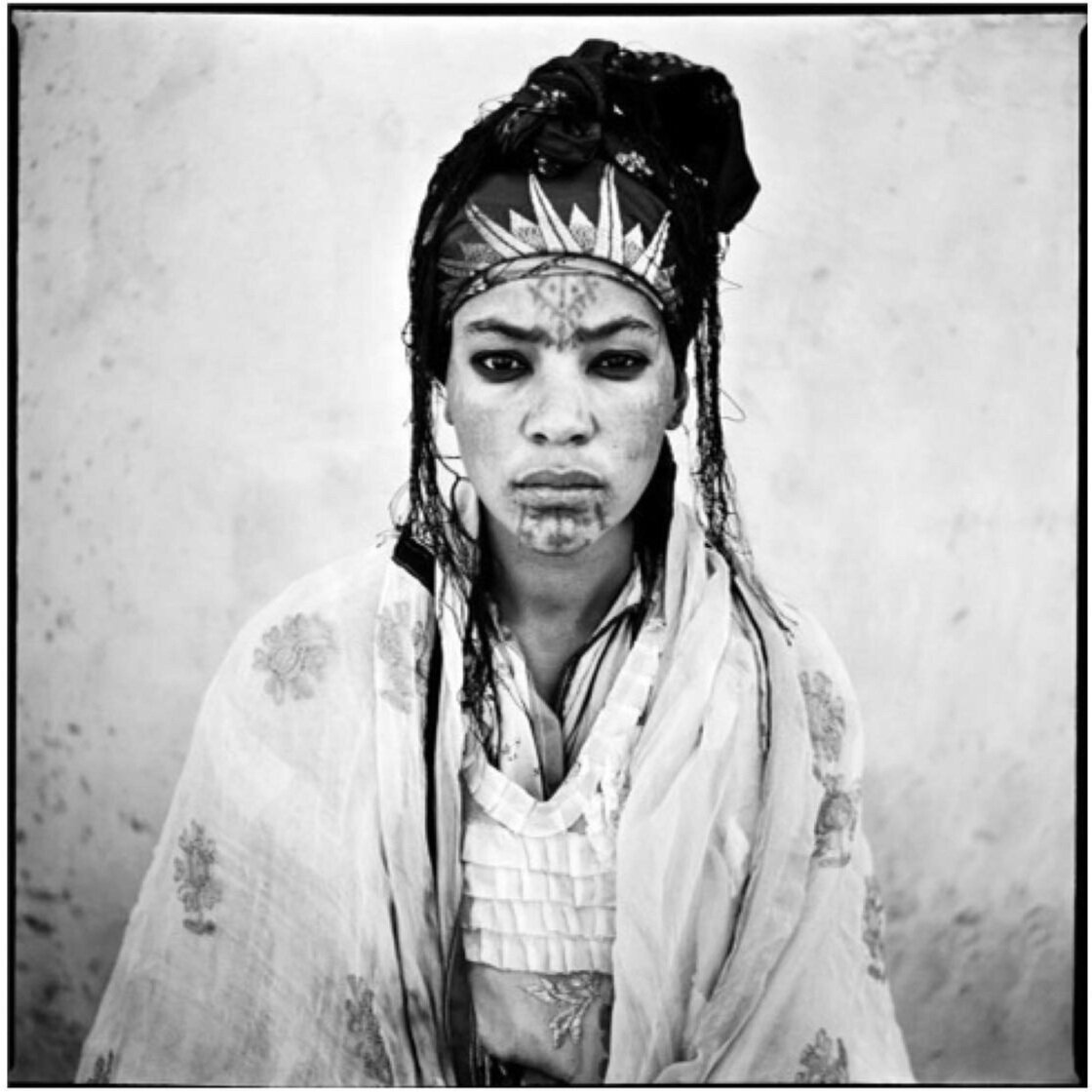

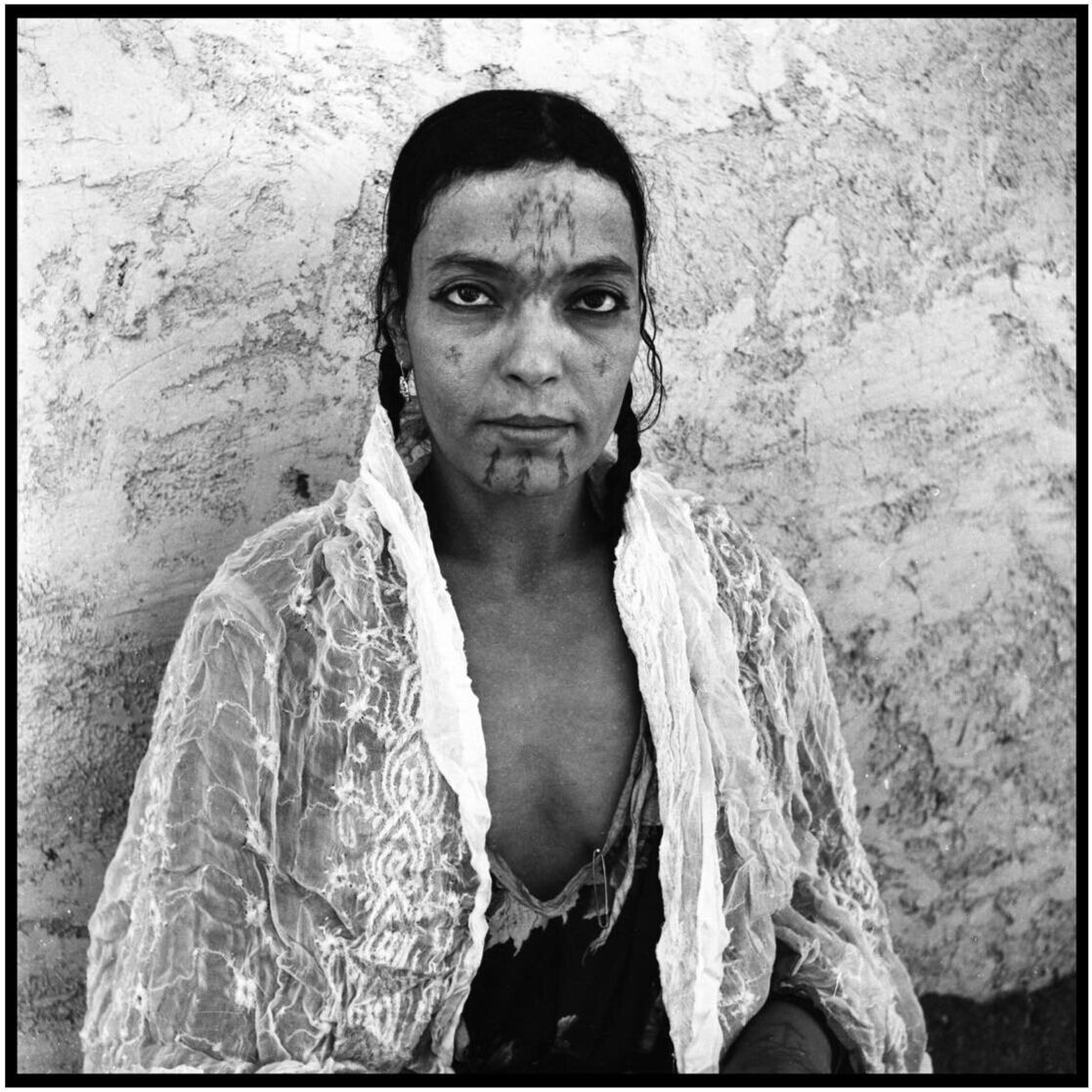

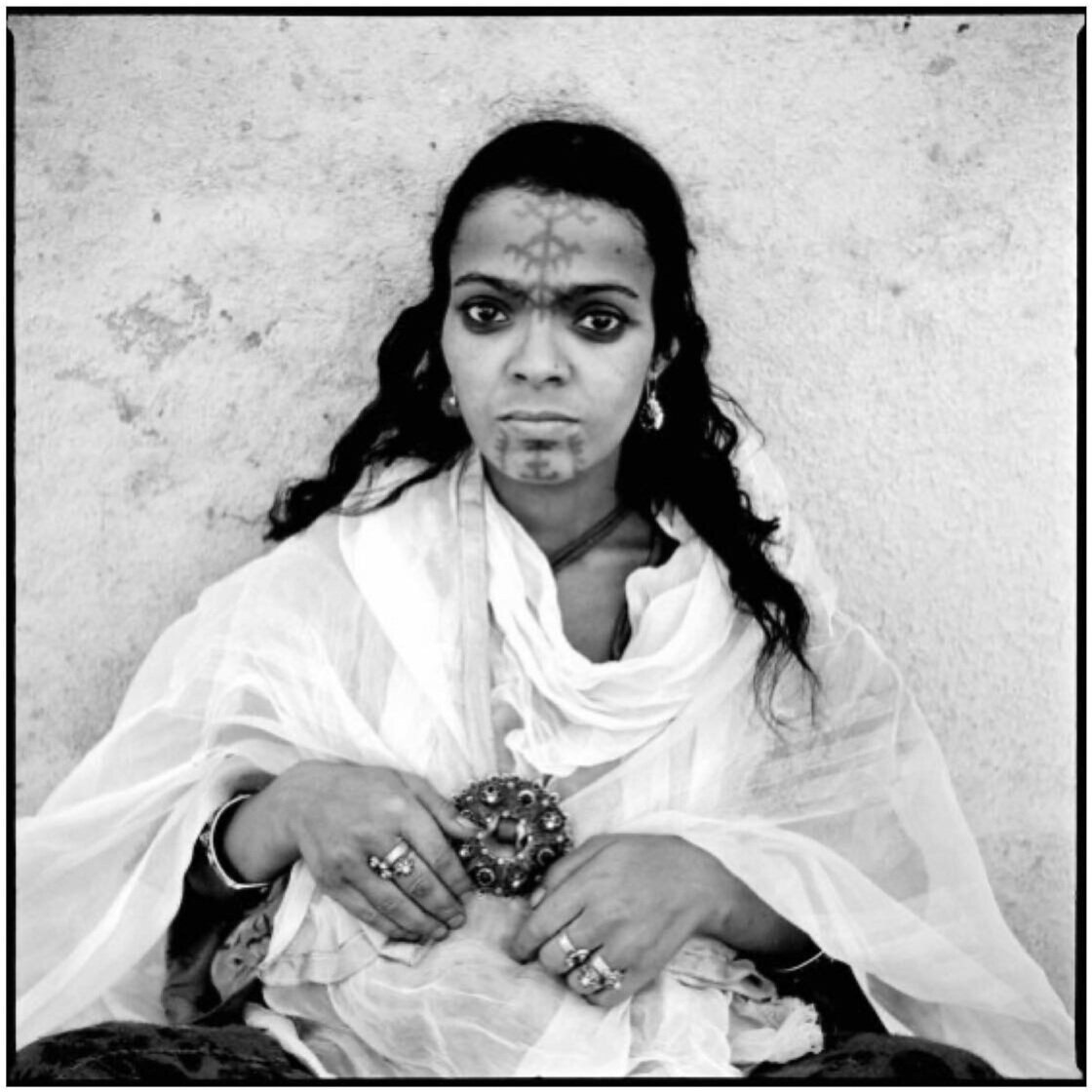

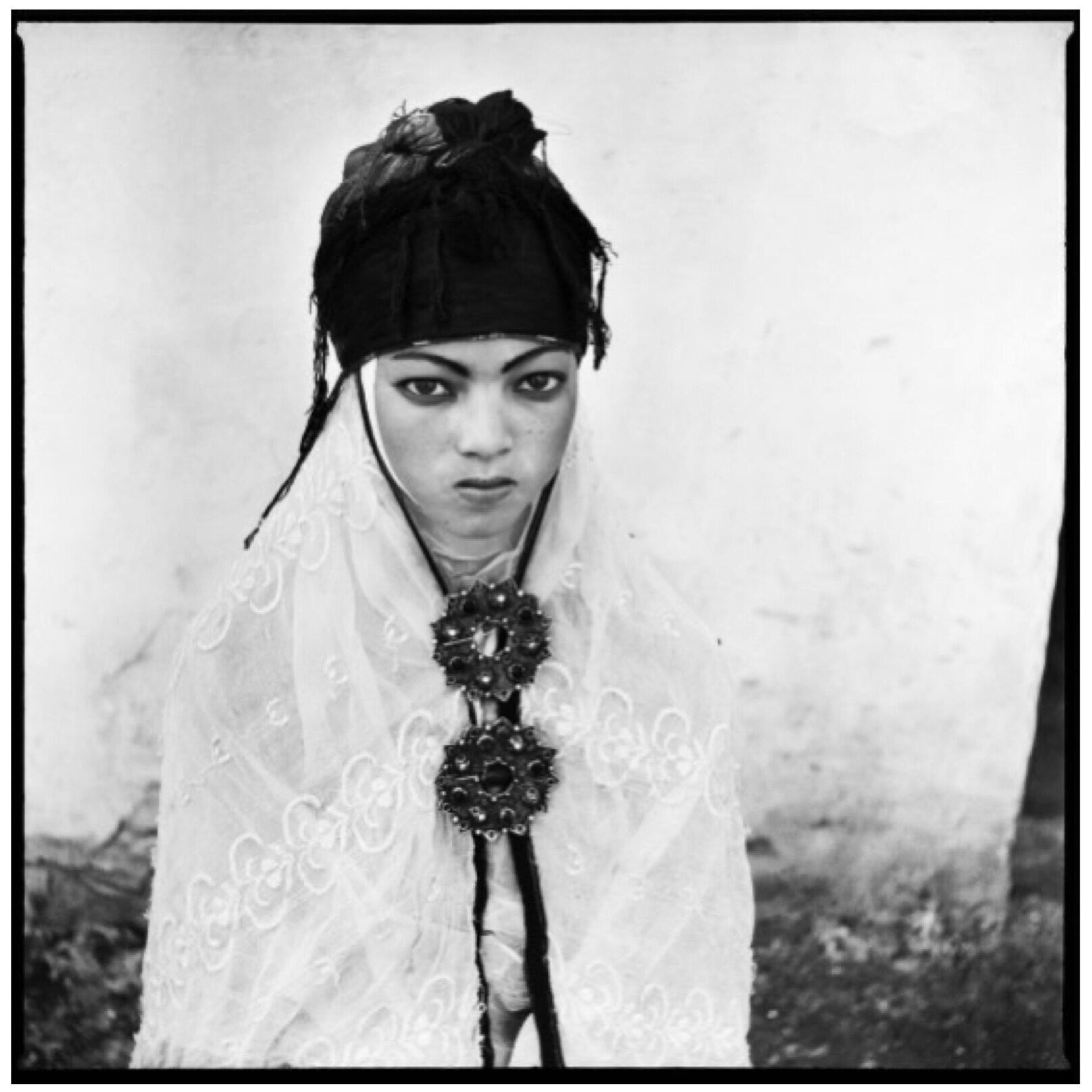

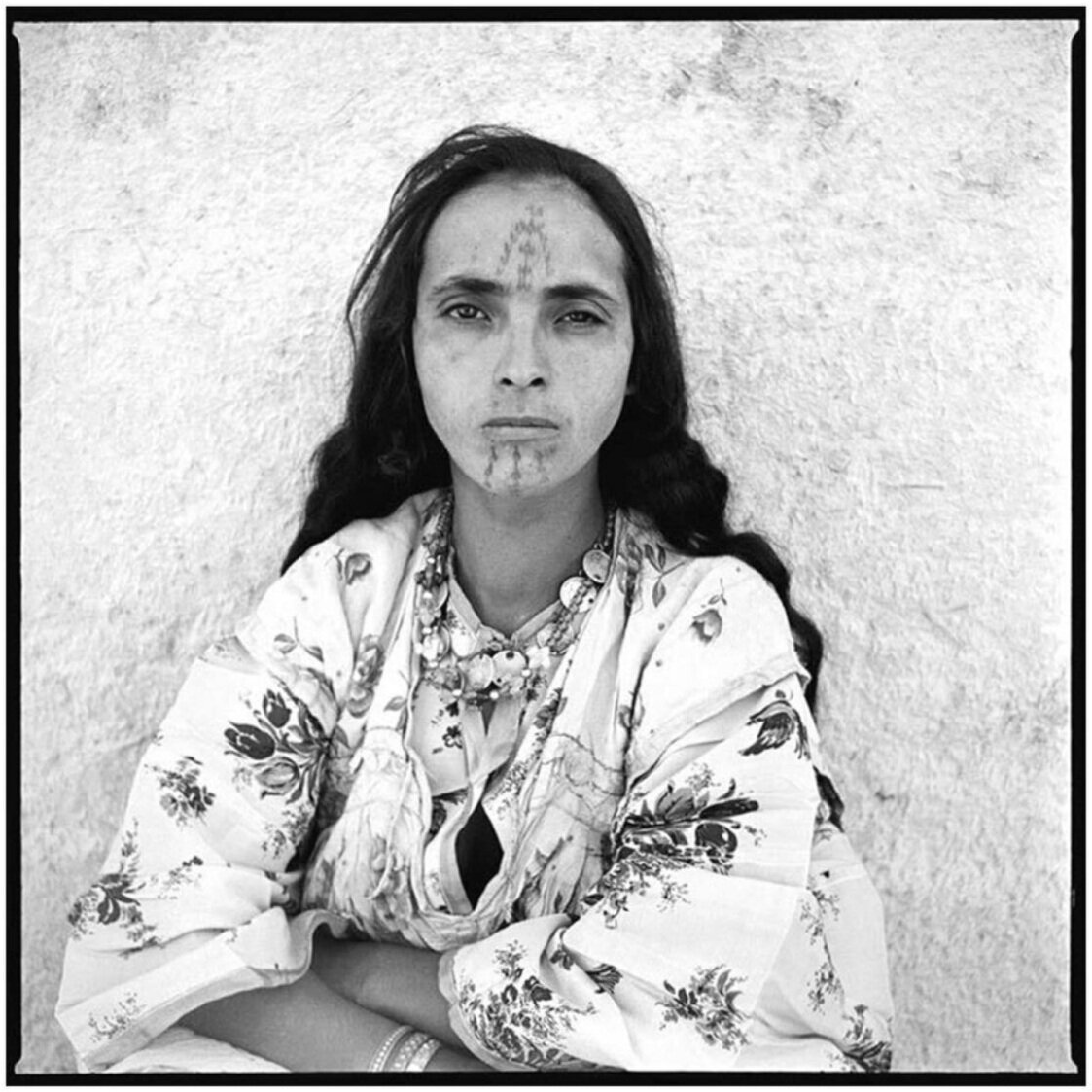

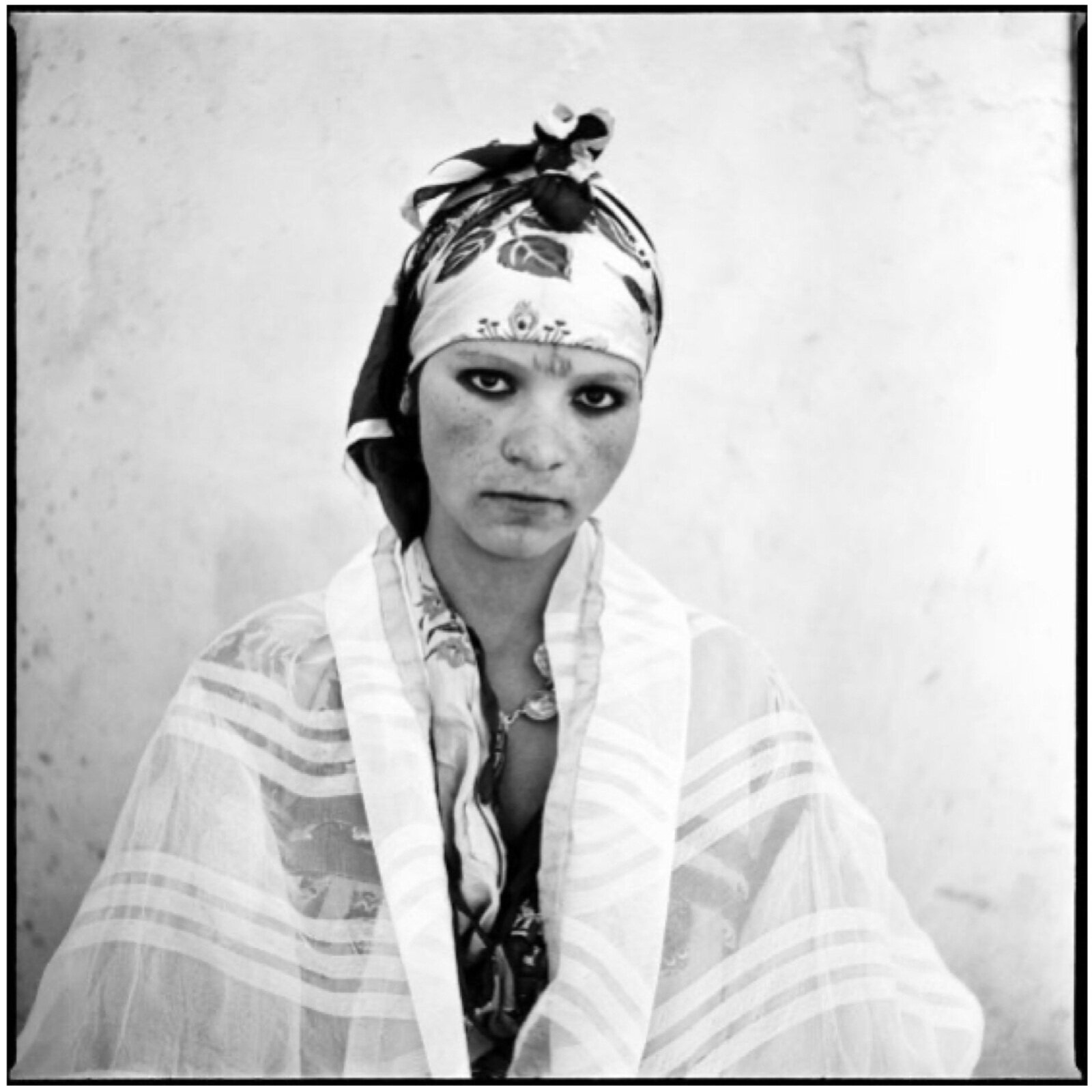

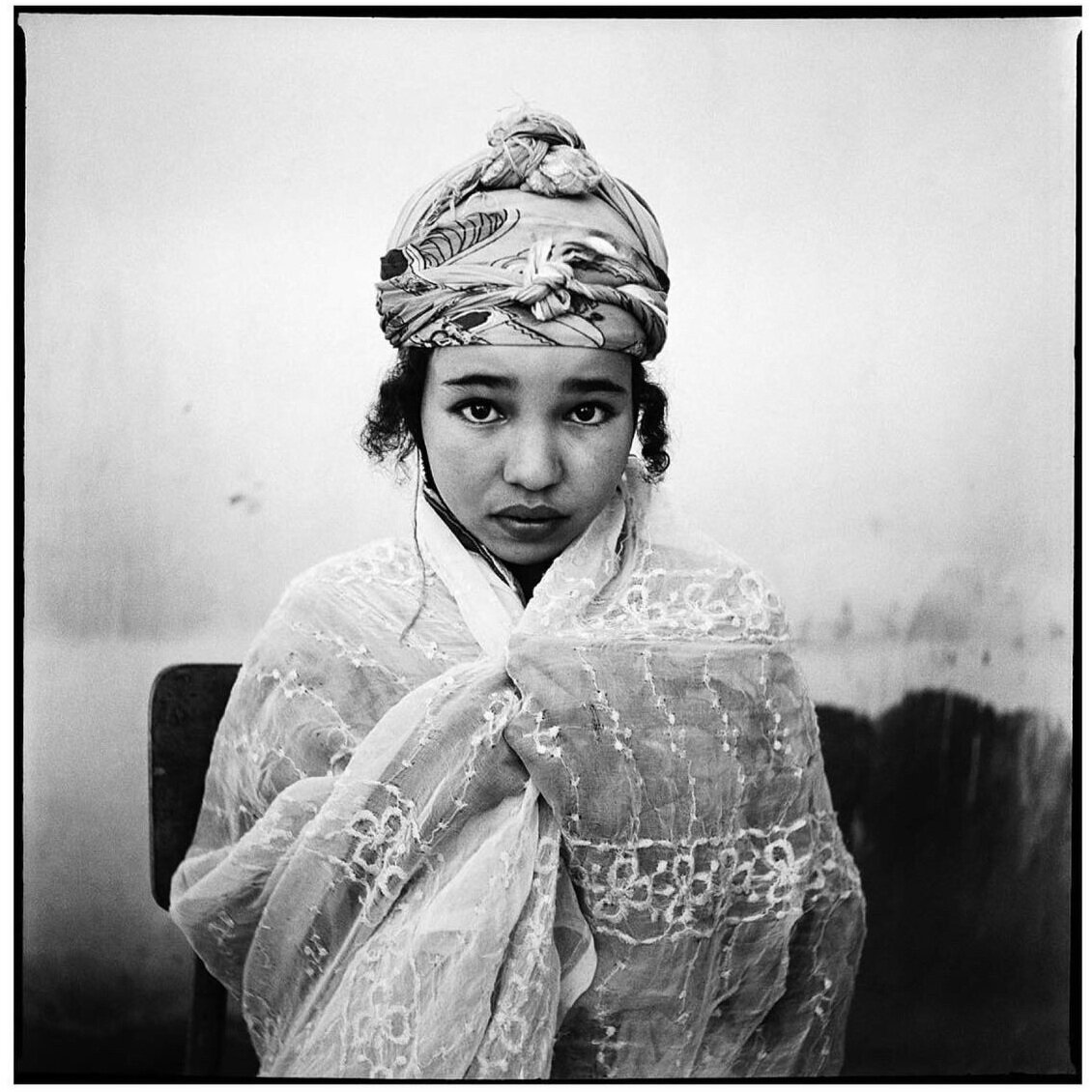

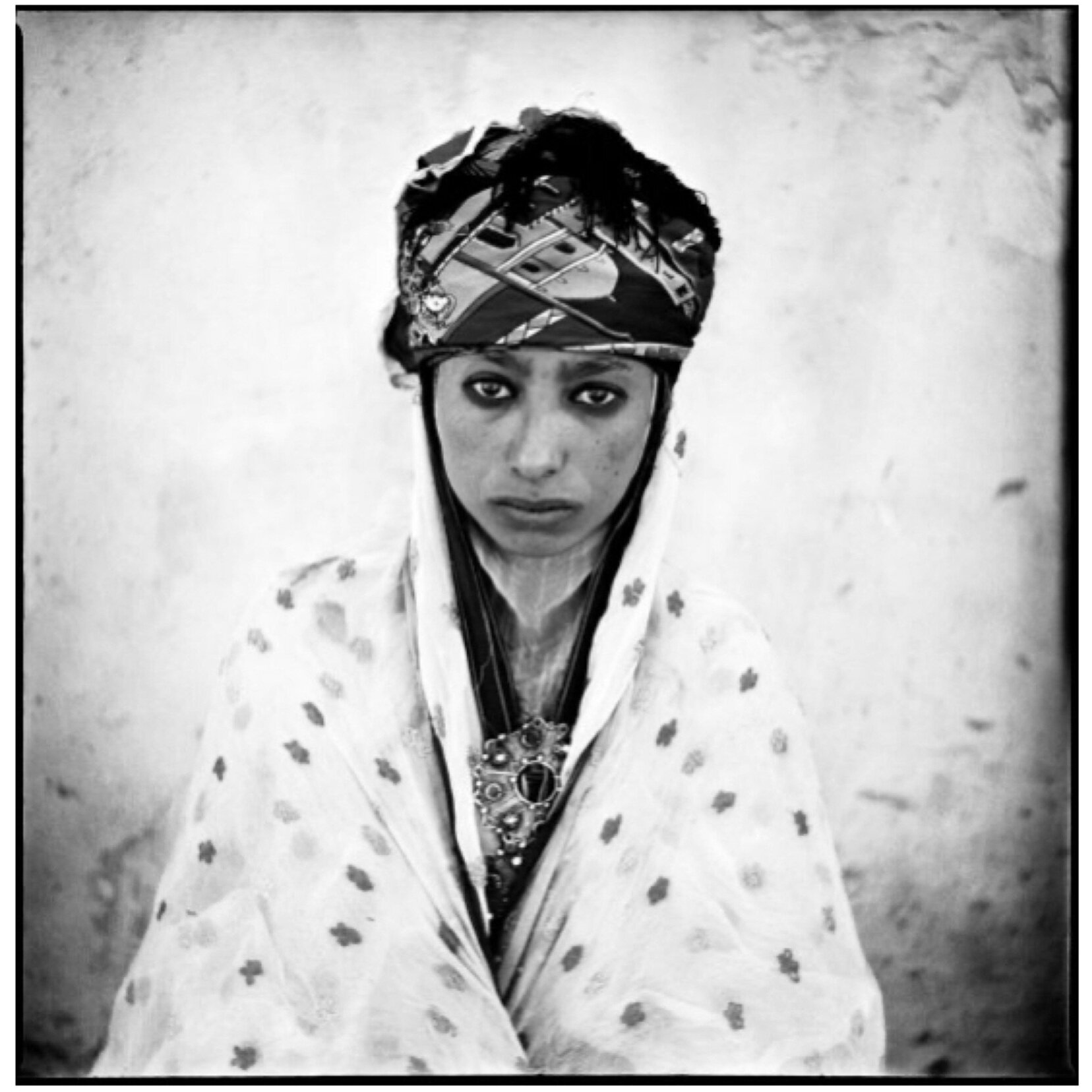

The gazes of these Algerian women have been etched in my memory ever since I first saw them, years ago.

I hate these portraits and admire these women.

The photographs were taken at Ain Tezine (Kabylia), in 1960 by photographer Marc Garanger, ordered to do so by the French army that had been occupying Algeria since 1830. By that time, France had been attempting to suppress the Algerian war for independence for several years and they were arresting and imprisoning entire populations of Muslim and Berber villages for suspected support of the insurgent National Liberation Front. Their villages were destroyed and their people were transferred into concentration camps.

When the army decided that all ‘resettled’ people should carry mandatory ID cards, Marc Garanger was tasked to photograph around two thousand portraits during ten days of stay in the area. As most men had enlisted with the rebelling NLF, it was mainly women that were captured, in real life and on film.

These women had never before come into contact with Europeans.

They were forced to remove their veils and headscarves, revealing their hair, skin and protective tattoos for the first time outside of the privacy of their homes.

They were to sit on a stool in front of a whitewashed wall while a stranger, accompanied by armed soldiers with machine guns, came uncomfortably close and pointed an unknown instrument at them.

This camera, is what they confronted: quietly, but most certainly not silent.

In her 2017 book Listening to Images, Professor Tina Campt explores a way of listening closely to photography and explains how “photographs originally intended to dehumanise, police, and restrict their subjects, can convey the softly buzzing tension of colonialism, the low hum of resistance and subversion, and the anticipation and performance of a future that has yet to happen.”

Two years after these photographs were taken, in July 1962, Algeria would finally have its hard-won independence.

When these women gazed back, it was in the anticipation of that victory.

And maybe it wasn’t the eyes that lingered with me all those years.

Perhaps it was their hum.

It is worth adding that Marc Garanger, a pacifist, tried to mirror his opposition to the war, as well as his respect for the subjects, by not just taking identity snaps but by framing dignified portraits at the waist. Attempting for his photographs to bear witness and hoping that they could one day bring awareness and lead to action against this human rights abuse.

In 2004, Garanger returned to Algeria to meet with the women he photographed almost half a century before.

This time, he was welcome.

xez

Zohra Gacem and her family in 2004, holding the identity photograph taken by Marc Garanger forty four years before.

Sources/Further Reading:

New York Times, Article 2010: Unwilling Subjects in the Algerian War

TIME, Article 2013: Women Unveiled: Marc Garanger's Contested Portraits of 1960s Algeria

TIMELINE, Article 2016: These Algerian women were forced to remove their veils to be photographed in 1960

How I met Marc Garanger and how the Algerians he had photographed welcomed him 50 years later, by Fatiha Saou

Burning the Veil, the Algerian War and the ‘Emancipation’ of Muslim women 1964-62 by Neil Macmaster